I was driving to my office on Monday morning when the phone rings. One of our church members tells me a family member tested positive for COVID, so they’re quarantined for 14 days. They call me back 45 minutes later and said they were let go from their job. A staff member walks into my office and says another one of our members is completely out of work because their company is shut down because of COVID. I get a call from an entrepreneur who says the market has virtually dried up – they’ve got zero work coming in. It’s a terrible Monday morning. It may be true that COVID stole their jobs. But for a disciple, COVID can’t steal their vocation for their occupation. COVID has exposed the gaps that have already existed in transformational and biblical discipleship. The reality is our mission as pastors is to equip the saints for the work of ministry (Eph 4:12-16) not within the walls of our churches, but in the context of their work. If we don’t know what our people do to make a living the other six days, and how the characteristics of a disciple play out in the real world, I would suggest that we are in trouble. Public intellectual Charlie Self says, “We must prepare people with vocational clarity and occupational flexibility”. Vocational clarity is about a sense of calling that every believer has heard from God about their specific purpose in the Kingdom. We have all been given unique gifts and talents and a divine design that benefits us, our families, our communities and as we seek the common good. As we think about vocational clarity we think about the dignity of our work and how that matters, but it goes much further than a job. It’s about the long game of who we are at the core, whether we are a big picture visionary, a detailed analyst, a relationship seeker, or a natural contributor. Vocational clarity also plays itself out in our mission with spouse and how our teamwork is guided by the Holy Spirit. Occupational flexibility is about how our practical skill sets accomplish our vocational clarity. In other words, our occupational flexibility is how we use our hard skills in different and creative ways to adapt to changing market conditions like those posed by COVID-19. If your vocational calling is being an artist or being a creative thinker, your occupational flexibility is about using your hard skills in construction or woodworking, deck building, plumbing, designing organizations, solving very complex problems, applying digital algorithms, or working the budget so that there’s a dynamic financial velocity. Occupational flexibility is the practical and hard skill sets that can be applied as a master tile cutter, your brilliance on excel spreadsheets, economic modeling, electrical work, or solving complex legal problems. It’s the millwright who can machine at a very detailed level for minute tolerances to build a custom steam furnace. It is the discipline of expanding and honing your practical skill sets that creates your occupational flexibility. When you have occupational flexibility, work becomes a matter of location and preference. You get to choose how you fulfill your vocational clarity and apply your occupational flexibility within the work that you are able to do. As a disciple we understand the divine design at a deep personal level creates vocational clarity. But the disciple also has to seek the guidance of the Holy Spirit to develop occupational flexibility. That’s when work is no longer a chore but a joy. Work then adapts to the location and context of what and where you want to spend your time. The reality is COVID may have stolen your job, but nothing between heaven and hell can steal your God given vocation (i.e. your divine calling). Your occupation is a matter of navigating and honing your practical skill sets. Once you’ve achieved vocational clarity and you develop occupational flexibility with your practical and hard skill sets, your work becomes a creative act of worship unto God, and no virus can steal that from you! The Discipleship Dynamics Assessment TM is a discipleship tool that allows you to measure your discipleship progress in four of the Discipleship Outcomes that are mentioned in this blog (see the Outcomes in italics). Jamé Bolds, Ph.D. Candidate (Universiteit Stellenbosch) is the lead pastor of Victory Church, Yorktown, VA as well as an adjunct professor at Gordon-Conwell. He writes on Pastoring Faith, Work and Economics at jamebolds.com This article was originally published on July 21, 2020 on Discipleship Dynamics, LLC blog.

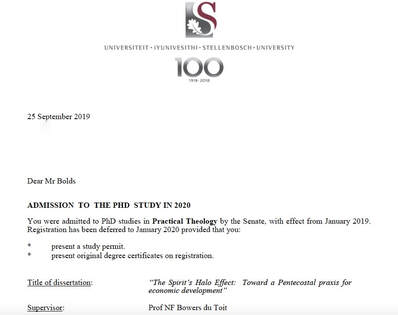

Reprinted with permission. https://discipleshipdynamics.com/blog/  My 2019 Ph.D. Universiteit Stellenbosch acceptance letter. My 2019 Ph.D. Universiteit Stellenbosch acceptance letter. Since this COVID-19 crisis it has had an untold impact on Christian higher education. The real impact has been the real personal impact on the students and my professor friends. What got me thinking was my alma mater Southeastern University just laid off 34 professors. Let that sink it -- 34 professors lost there jobs. Wow. During this time I started to rethink why am I getting a Ph.D? And I've come to the simple conclusion: I want to. I want to solve a problem. And I like it. I'm so for my friends that are like me working towards a ministry focused Ph.D. (Bible, theology, or ministry) and those who are thinking about it -- here's some thoughts that I really wrestled with. So hear me clearly, I really don’t want to be a wet blanket, a dream crusher and I say my comments as a doctoral candidate myself. I'm simply sharing my own questions and observations, so here you go, hope it helps. 3 Considerations Why You Shouldn't Do a Ph.D.

1.) Professional Life. Frankly there are very few jobs that pay full employment as a professor preparing people for ministry. They simply don’t exist and if they do it's tied to a one year contract and you can be let go at any point (broadly speaking, of course there are exceptions). That's a tough life. 2.) Financial and Professional Cost. If you do a ministry focused Ph.D. you should absolutely not pay a dime for that degree. You should either have a full ride, a foundation/grant/job or rich uncle to pay for it. The economics simply don't work. Why would you do a Ph.D. in New Testament or practical theology and pay $85,000 for it when you "might" get a job making $65,000, and be employed on a renewable one-year contract. Then go to compete in a job market that isn't there because Christian institutions of higher education are not growing, and you're going to end up being an adjunct professor for five different schools to cobble together $34,000 a year, teaching 10 courses, without insurances, or retirement ? Welcome the job market - If you're lucky. 3.) Ivy League. If you do a Ph.D. and it happens to be at an Ivy League you might be able to compete in the market but you have to be absolutely extraordinary. I personally know a few PhD’s from top 10 schools that were not hired on as full-time faculty. They are in fields like economics, public policy, and management science, and of course ministry. Now those friends of mine found work in business, government and research but they didn't find an academic post. My ministry Ph.D. friends are still looking. The #1 Consideration Why You Should Do a Ph.D. Personal Mission. You want to. You want to solve a problem. And you like it. There is only one reason to do a Ph.D. and that’s because you want to. You want to add to the body of literature on a subject and advance human knowledge. AND you view your Ph.D. research and teaching as a professional hobby, something to fund your retirement, vacation money or you need to remodel the kitchen. You don’t do it for a job; you don’t do it because you want to be called “Dr”; You don’t do it because you wanna impress your parents or your kids. You do it because you have a problem and you wanna solve it and it’s 100% for personal mission. (And hopefully you save the world in the process.) Well there's my 2 cents. I hope it was helpful and gave you some things to wrestle through. If you disagree with me, that's ok. It's my day off, now, I need to go work on my dissertation. Love ya! April 16, 2020, Washington D.C. The Center for Public Justice spotlighted Victory Church as a Sacred Sector Partner. The Sacred Sector is a learning community for faith-based organizations and emerging leaders within the faith-based nonprofit sector to integrate and fully embody their sacred mission in every area of organizational life. The original article is located here.  COVID-19 & Public Justice BY JAMÉ BOLDS AND CHELSEA LANGSTON BOMBINO Victory Church in Yorktown, Virginia is a congregation within the Assemblies of God fellowship whose mission is to “invite people to discover Jesus in everyday life.” This church emphasizes a holistic, incarnational gospel in its organizational core values to:

Victory Church is a 2018-2019 Sacred Sector Community participant, and has long shared a mutually beneficial relationship with the Center for Public Justice (CPJ), started through Victory Church Pastor Jamé Bolds. Through a mutually beneficial collaboration, Victory Church and Sacred Sector (an initiative of CPJ) strengthen each other as they seek, in community with other congregations and faith-based organizations, to live out their sacred animating beliefs, in every area of their organizational lives - even amid the current COVID-19 pandemic. Lead Pastor Jamé Bolds, along with Missions Pastor Mark Shanks, approaches this current pandemic as an opportunity to live into his congregation’s faith-based commitments in everything they do, fulfilling their God-given responsibilities with respect to how they engage their own faith community, how they serve their broader Virginia community, how they coordinate with other congregations and community-serving organizations, and how they interact with government. I (Chelsea Langston Bombino) first met Pastor Bolds a decade ago when we were both participants in the Center for Public Justice’s 2010 Civitas summer program. Civitas was a leadership program CPJ provided for a number of years, offered to graduate students, Ph.D. students and other young adults interested in civil political engagement. At the heart of the program, academics and future church, policy and government leaders came together in community to learn how a public justice framework in the Kuyperian principled pluralist tradition shapes every area of life. Civitas provided a philosophical and theological framework for living out a public justice framework for how Christian citizens could engage in political community, and offered participants the opportunity to apply this framework to their own academic research or distinct roles in the varied vocational offices in civil society. Sacred Sector is also a learning community within CPJ which empowers participants, in this case faith-based organizational leaders, to apply a public justice perspective to their specific context. Sacred Sector uses a holistic framework to empower faith-based organizations and their leaders to integrate their faith into everything they do: 1.) how to understand and respond to public policies that impact their faith-based work, 2.) how to implement organizational best practices to advance their faith-based missions, and 3.) how to publicly position their faith-based impact. Sacred Sector calls this framework the “Three P’s,” empowering its participants to incarnate their sacred institutional identities (both their freedom and their responsibilities) in six key areas: religious staffing, government partnerships, positive engagement in the public square, sexual orientation and gender identity nondiscrimination laws, advocacy and lobbying, and family-supportive workplaces. This “Three P’s” framework and Sacred Sector’s resources are especially relevant in this moment of living into our faith during COVID-19, as Pastor Bolds highlights in our interview below. He emphasizes that while religious freedom is a foundational value, it is a false appropriation of religious freedom when churches claim that following public health guidance meant to protect all of our communities, especially the most vulnerable, is somehow a violation of that freedom. To the contrary, Pastor Bolds encourages us to use “Spirit-filled logic” in navigating when we ought to prudentially claim our religious freedom has been limited. Rather, he suggests that public policy, organizational practices and public positioning can all work together to strengthen an organization’s capacities to live out it’s religious responsibilities in this moment. Pastor Bolds now is the lead pastor of Victory and a Ph.D. candidate at Stellenbosch University. I interviewed Pastor Bolds (abbreviated as “JB”) and Victory Church Mission Pastor Mark Shanks (abbreviated as “MS”), to reflect on how Sacred Sector and Victory Church are helping each other to mutually grow in their capacities to advance their ministry’s mission: Chelsea Langston Bombino (CLB): Pastor Bolds and Pastor Shanks, tell me a bit about how you view your vocational office in this church. Jamé Bolds (JB): I do three things: I envision; I teach; I form leaders (networking). I love my Victors (those who call Victory Church home) and I’m consumed with helping you discover Jesus in five areas of your life: Discover Jesus (Spiritual Formation), Discover Myself (Personal Wholeness), Discover Others (Healthy Relationships), Discover Purpose (Vocational Clarity) and Discover Work (Economics). We have a way to help you discover those things; we call it the Victory Way. In 2020, we’ll be driving down this discipleship path which will help you grow in every aspect of your life. Mark Shanks (MS): I was in a Guatemalan jungle when God revealed to me that I was called to pastor missionaries and expose people to the global God of Acts 1:8. Here at Victory, I’m the outreach champion, responsible for having our church act as a "neighborhood to nations" as we support the work of our missionaries. My heart is to spread the good news globally, caring for missionaries that may feel isolated or discouraged. In this moment of COVID-19, we are exercising what we call "Spirit logic,” or being led by the Holy Spirit, to navigate our church-based roles and responsibilities. Our congregation has moved to remote work, but that is a (metaphorical) floor, not a ceiling. Our childcare is also suspended for now, for the health and safety of our families. But it is not enough for churches to stop at practicing public health guidelines. We are called as the body of Christ to carefully consider how we can offer spiritual, physical, and relational resources to our communities, in coordination with others. Our spiritual calling, and our freedom to serve, during COVID-19, does not change; what changes is how we are called to innovate in how we exercise our religious freedom in a way that helps and does not harm our communities. CLB: Can you give a picture of what Victory’s past, present and future hold? How does this relate to how it continues to be a congregation that seeks to embody its sacred purposes in everything it does? JB: We are a fifty-year-old Assemblies of God congregation who has moved in three different locations over the past fifty years. My predecessor was here for the past twenty-five years. Our previous pastor had a vision for what church life would look like in twenty years and I really believe God gave him the bigger vision of this ministry. I often feel like Joshua finishing Moses' work. Just in terms of numbers when [Mark and I] came in, we had 28 people. We were losing $100,000 a year, and the church's preschool was basically broke. The building was pretty much in disrepair. The church had $1 million in debt. When I started, my main resources available to me were spiritual resources: the Holy Spirit, God’s word, God’s grace, and a bunch of prayer! I knew when Pastor Jennifer and I came to Victory that God had called us to pastor a city, not just a church. Understanding your spiritual identity and foundational sacred beliefs are crucial. You can’t live out what you don’t understand and articulate. We had very little technique, but by God's grace five years later the building is completely rebuilt, we are at capacity in the preschool, we are 100% debt free, the congregation has grown by 300 percent and Pastor Mark has come on board as our Missions Pastor. The theological and practical turning point to church revitalization was when we started to tithe to missions. We wanted to be a church that was embedded in our community. We now have a foundation that will keep the church going in perpetuity. At a Christmas party, Mark walked up to me and said: "I want to be a Missions Pastor." So Mark came into a residency for two years and then became a Missions Pastor. The model of giving that Victory has undertaken is based on God’s word. We seek to embody the same values Sacred Sector espouses when you talk about incarnating your sacred texts and beliefs into your institutional practices. We think what we have could really be a national model for giving. Acts 1:8 states: “But you will receive power when the Holy Spirit comes on you; and you will be my witnesses in Jerusalem, and in all Judea and Samaria, and to the ends of the earth.” This is the vision of how we tithe, we believe our missions work must be investing in Jerusalem (local community), Judea (our larger region) and throughout the world. When we were putting this together, Mark and I came to the conclusion that it was really a team effort. Most churches would only give between $20-$50 a month per missionary. We know that it costs missionaries a multiplier by three to raise the money -- so it will cost a missionary 50 to 75 dollars to raise 20 dollars. We look at two things: (1) Do we have a relationship with you, and (2) are you effective? We want to build a relationship with you if you are effective. So we started to give a substantial amount of money to fewer missionaries who are doing what no one else does, and who know how to measure their effectiveness. We want to plant good seeds in the ground and it is not just going to help anyone just sitting at the church - the simple concept of sowing and reaping. We started applying sound neo-liberal economic theories to missions and developed a sustainable economic model. During COVID-19, principled pluralism is a very powerful framework, and it guides everything I do, including how we prioritize missions during this time. If our congregation and our missionaries can understand the normative framework and the nomenclature of principled pluralism, they will be able to see why it is so vital during COVID-19 that they not just evaluate their own distinct God-given gifts and way they can serve in this moment as individuals, whether they are local, national, or throughout the world, but it is essential that they can have a vision for the institutions and communities of which they are a part, and those around them. Principled pluralism requires that missionaries navigating COVID-19, no matter where they are, think about how they can help their institutions develop and innovate new means and norms to live out their God-given roles. Mark Shanks (MS): It was a walk of faith. It was a marriage basically. I had been in three different churches and I saw things that could have been improved about the outlook. Jamé started his career at a think tank, so he brings those economic and philanthropic ideas and things just started joining together. And then when I started really talking with missionaries and other churches, there was this difference that says "oh yeah, we give to missions." The radical element of change was Malachi 3:10 (NASB): “Bring the whole tithe into the storehouse, so that there may be food in My house, and test Me now in this,' says the LORD of hosts, 'if I will not open for you the windows of heaven and pour out for you a blessing until it overflows.” We started seeking the Lord to help us incarnate this vision of this verse in our congregational missions practices. We started asking, what does it look like to tithe your income to missions according to this verse? Why doesn't the church tithe to missions? They have an income coming in, don't they? Giving is a benevolence thing to do. Tithing is a faith thing. JB: We look for creative innovation. We look to be strategic thought partners with the missionaries we support. We love missionaries who allow us to come to the table in thought leadership and strategic input. Our heart goes before the checkbook. With our missionaries, it is a culture of yes. CLB: Besides Victory’s missions work, can you discuss how your congregation has lived out its faith-based mission? JB: Especially with respect to COVID-19, there is a distinction between fear and caution. Fear is real, but we believe our Victors (congregants) don't give into a level of fear. And we certainly don't want to get into this whole "Well the government cannot tell me what to do because we are a church we can do what we want this is a religious freedom problem." Well, that is not accurate. This is not a religious freedom problem, unless the government singles out faith-based institutions. This is how the government is advising every institution in society. Christians should recommend their congregants be good citizens by following public health guidance and government recommendations. For example, the local Baptist church is handing out lunches where we live. I called them up and asked, "how can we help?" The Baptist church told us what they were doing was unsustainable, that they could only serve the local kids for two weeks without community partners. They had not necessarily thought through how to coordinate with local government or with other congregations and community-serving organizations. We suggested, what if each congregational community and faith-based organization and local government agency could bring their distinct assets to the table, the things they are most strong in, and coordinate together to serve the community holistically? Our Baptist friends did an amazing job filling the gap between the private and public sector now the local schools were caught up in there lunch program. Even before COVID-19, our congregational leadership has tried to live into this vision of coordinating institutions to live out their God-given roles. We have grown; we own over 20 acres, we have a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) with the YMCA. We are talking about a second site for preschool, and are in negotiation with an elderly care organization. As we have grown, CPJ’s philosophy has helped us navigate the interconnectedness between our ministry and the public square. We are living that out. We lost a deacon who said that churches should not have any community partnerships, and they simply did not support our collaboration with the YMCA. It was sad and we mourned the loss. The perceived sacred and secular divide is real and we simply believe that all of the created order is sacred. Every square inch. CLB: By engaging in mutually beneficial strategic partnerships with groups like Victory, and with the strategic input you both bring, Sacred Sector will be able to more clearly integrate a biblically rooted framework into everything we do. Victory and CPJ share a vision of mutually refining one another through our collaboration with one another. We are engaging as co-investors and as co-laborers in catalyzing institutions and individuals with the capacity to engage in policy-shaping aligned with a principled pluralist framework. Through the process of shaping Sacred Sector’s resources to reflect a biblically rooted, principled pluralist framework, leaders will in turn be strengthened to engage more fully in both their own scholarship and citizenship in the support of a robust and diverse faith-based social sector. What can Sacred Sector keep doing to deepen our partnership with you and other congregational communities like yours? JB: I would like to see more legal templates and case studies. I think we could develop more practical language for how churches can navigate this space. We really valued CPJ’s eldercare resource in 2019. We just launched an opportunity for a $31 million retirement community. CPJ's research, principles, and case studies on eldercare have really inspired us to keep pursuing this work. The book of Habakkuk speaks all about disease and pestilence. And Habakkuk asks in the first two chapters: "Why does this happen, why?" And in chapter three God tells him he is going to write the vision for peace and redemption down, in the midst of peace. Principled pluralism gives us public language to speak to people. As a local church, what can we do to advance the common good? What is the common good? As Christians, that is a beautiful place to be, because you can't have the common good without the Good News. You can't have the Great Commission without the Great Compassion, it doesn't exist; it is contrary to the Christian faith. ______________________________________________________________ Jamé Bolds, Ph.D. Candidate (Universiteit Stellenbosch) is the lead pastor of Victory Church (Yorktown, VA). Chelsea Langston Bombino is the director of Sacred Sector, an initiative of the Center for Public Justice. Here's an excerpt from my paper, A Case Study in Practical Theology, Addressing Economic Violence Towards Women: Three Considerations, which will be presented at the Society of Pentecostal Studies, in Los Angeles. A working theological female anthropology served as a theological motivation that calibrated our applied economic wisdom. Broadly speaking economist talk about the notion of homo economicus as a concept of viewing human beings as rational and self-interested individuals who purse wealth solely by maximizing outcomes. It is considered to be first used by John Stuart Mills in 1836, in an essay “On the definition of Political Economy and on the method of investigation proper to it". Where he states, "[Political economy] does not treat the whole of man’s nature as modified by the social state, nor of the whole conduct of man in society. It is concerned with him solely as a being who desires to possess wealth, and who is capable of judging the comparative efficacy of means for obtaining that end." [1] Adam Smith states, “It is not from the benevolence of the butcher, the brewer, or the baker that we expect our dinner, but from their regard to their own interest.”[2] As much debated as this concept is and that many sociologist, psychologists and economists argue that there are structural impediments to why self-interest is not carried out or simply disagree with the anthropological construction. The reality is though most economic life is based on this notion. A significant pastoral challenge arises when working with these women through an “economic salvation experience”, if you will, which is one moving them from homo economicus, “I work to survive” to a homo imago Dei reality of “I am made in the image of God and I have a part of a flourishing in this world”. Brian Fikkert, of the Chalmers Center states, “…Economic exchange is essential for human flourishing, enabling humans to specialize according to their individual gifts and callings in order to jointly steward God’s creation.”[3] Helping these three women to think deeply and spiritually about how they are made in the homo imago dei and the image contribution looks like in an economic exchange for their flourishing of their families. This has been a turning point not only in their practical economic life but in their spiritual formation.  Much of our historical understanding of the imago dei has been built around male identity and then described in language of “subduing” the earth. This is been a pastoral blind spot for myself because I have never really thought about female notions of imago dei until I came to this point with these three women. This experience has forced me to think differently and see imago dei in terms of relationship. Megan DeFranza notes, "Although he was not the first to do so, Karl Barth (1886-1968) is often credited for challenging the traditional interpretations of the imago Dei. Rather than understanding the image as the soul’s ability to reason, or human responsibility to rule over creation, Barth looked to the creation of Adam and Eve as a symbolic picture, an image of the Trinity. In Genesis 1:26, God said, “Let us make humankind in our image,” and then what does God make? Not one but two, a man and a woman, who are to “become one flesh” (Gen. 2:24 NRSV). Just as God is a plurality and unity, three in one, so humankind, created in God’s image, exists as two who are called to become one. Thus, after Barth, we find that human sex difference and human sexuality (the means by which these two become one) are being taken up into theological accounts of what it means to be made in the image of God.[4]" Mary McClintock Fulkerson notes that the image of God is a weighty doctrine because “the image is a symbolic condensation of what in the Christian tradition means to be fully human. In important respects the imago Dei can serve as an index of whom the tradition has seen as fully human.”[5] Such a thought is a pastoral reality check and especially important for Pentecostal praxis in church life. As Joy Qualls, of Biola University recounts us, “In the early years, Pentecostalism was committed to all people as equal participants specially the marginalized. Women, the poor, those with little formal education, people of color worked and worship with people of financial means and cultural status. Each had a place in an obligation and spreading the Pentecostal message”.[6] As we were given pastoral permission to be involved at a deeper detail of these women’s lives, we began to see the subversive nature of what we were attempting to do. I remember clearly there was a time in reflection where I came to grips that it is not enough to care for the spiritual and emotional life we must have direct intervention and these women’s economic life. One of the matriarchs of our modern Pentecostal movement Cheryl Bridges John’s notes that Pentecostalism is subversive and revolutionary movement, had a dual prophetic role: denouncing the dominant patterns of the status quo and announcing the patterns of God’s order.[7] These women benefited greatly when we begin to operationalize these new patterns of God’s order. [1] Mill, John Stuart. "On the Definition of Political Economy, and on the Method of Investigation Proper to It," Essays on Some Unsettled Questions of Political Economy. [2] Smith, Adam. “On the Division of Labour,” The Wealth of Nations, Books I–III. 1986 [3] Brian Fikkert and Michael Rhodes, "Homo Economicus Versus Homo Imago Dei," Journal of Markets & Morality 20, no. 1 (Spring 2017 [4] DeFranza, Megan K. Sex Difference in Christian Theology: Male, Female, and Intersex in the Image of God, 2015. [5] Mary McClintock Fulkerson, “The Imago Dei and a Reformed Logic for Feminist/Womanist Critique,” in Feminist and Womanist Essays in Reformed Dogmatics, 95. [6] Qualls, Joy E. God Forgive Us for Being Women: Rhetoric, Theology, and the Pentecostal Tradition, 2018. [7] Johns, Cheryl B. "The Adolescence of Pentecostalism: In Search of a Legitimate Sectarian Identity." Pneuma 17, no. 1 (1995) For a decade, I have been a member of the Society for Pentecostal Studies and have enjoyed the unique mix that is church wo/men and traditional ivy league Ph.D. scholars. In 2020, the conference theme is "This is My Body": Addressing Global Violence Against Women, as I thought about the theme I began to realize that we at Victory Church live in highly military area and address this issue head on and we've had a few successes in this area. I think and write on theology and economics not women's issues. Though I'm experiencing and seeing there's real economic violence towards women and I should probably explore this space... I haven't written this paper yet but here's my opening thoughts. If you have any research on this I'd love to see it. Enjoy. A Case Study in Practical Theology, Addressing Economic Violence Towards Women: Three Considerations. Presentation Synopsis * Statement of Problem. Modern pastoral leadership's portfolio has expanded immensely. Such expansion has exposed a gap in both pastoral leaderships economic wisdom, and a theological calibration as applied to economies of scale in public ministry. Ethnographically, women continue to be silenced victims of economic violence in that they are not included in market activities thus structurally isolated from participation. Scope. This paper is a case study in applied practical theology toward economic violence to women. Over the past two years our church has learned lessons in applying theological reflection to three foundational economic principles: scarcity, efficiency and sovereignty in three different women's dangerous situations. Discussion of Methodology. Reflecting on ethnographic "going native" methodologies, our church has seen women's lives in desperate need of theological navigation within the modern economic terrain. When employing scarcity, efficiency and sovereignty our church has been able to bring women out of economic exile where they are now market active. Tentative Conclusion. Though we have been successful in three women's lives our church has learned that liberal economies of scale are unstable and fluid. When thinking theologically about scarcity, efficiency and sovereignty market forces can be anticipated but not in economies of scale. A contextualized theology of suffering has been discovered as we navigate creating markets of opportunity. |

bio:+ Economic Theologian |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed